Li-young

Lee

THE FATHER'S HOUSE

Here, as in childhood, Brother, no one knows us.

And someone has died, and someone is not yet

born, while our father walks through his church

at night

and sets all the clocks for spring. His

sleeplessness

weighs heavy on my forehead, his death almost

nothing. in the only letter he wrote to us

he says, No one can tell how long it takes

a seed

to declare what death and lightning told it

while it slept. But stand at a window

long enough,

late enough, and you may some night hear

a secret you'll tomorrow, parallel to the morning,

tell on a wide, white bed, to a woman

like a sown ledge of wheat. Oryou may

never

tell it, who lean across the night and miles

of the sea,

to arrive at a seed, in whose lamplit house

resides a thorn, or a wee man, carving

a name on a stone, at afluctuating table of

water,

the name of the one who has died, the name

of the one

not born unknown. Someone has died.

Someone

is not yet born. And during this black

interval, |

It's from Transforming Vision:

Writers on Art,

selected by Edward Hirsch

(Boston: Bullfinch-Little Brown,

1994) |

I sweep all three floors of our father's house,

and I don't count the broom strokes; I row

up and down for nothing but love: his for me,

and my own

for the threshold, as well as for the woman's

name

I hear while I sweep, as though she swept

beside me, a woman who, if she owns a face at

all,

it is its own changing; and if I know her name

I know to say it so softly she need not

stop her work to hear me. But when she lies

down

at night, in the room of our arrival, she'll

know

I called her, though she won't answer, who is

on her way

to sleep, until morning, which even now,

is overwhelming, the woman combing her hair opposite

the direction of my departure.

And only now and then do I lean at a jamb

to see'if I can see what I thought I heard.

I heard her ask, My love, why can't you sleep?

and answer, Someone has died, and someone

is not yet born. Meanwhile, I hear

the voices

of women telling a story in the round,

so I sit down on a rain-eaten stoop, by the saltgrasses,

and go on folding the laundry I was folding,

the everyday clothes of our everyday life, the

death

clothes wearing us clean to the bone, to the

very

ilium crest, where my right hand, this hand, half

crab, part bird, has often come to rest on her,

whose name I know. And because I sat down,

I hear their folding sound, and know

the tide is rising early, and I can't hope

to trap their story told in the round.

But the woman

whose name I know says, Sleep, so I lie

down

on the clothes, the folded and unfolded, the

life

and the death. Ages go by When I wake, the

story

has changed the firmament into domain, domain

into a house. And the sun speaks the day,

unnaming, showing the story, dissipating the

boundaries

of the telling, to include the one who has died

and the one not yet born. Someone has died

and someone is not yet born. How still

this morning grows about the voice of one

child reading to another, how much a house

is house at all due to one room where an elder

child reads to his brother, and that younger

knows by heart the brother-voice. How darker

other rooms stand, how slow morning comes, collected

in a name, told at one sill and listened for

at the threshold of dew What book is this we read

together, Brother, and at which window

of our father's house? In which upper room?

We read it twice: Once in two voices, to each

other; once in unison, to children,

animals, and the sun, our star, that vast office

of love, the one we sit in once, and read

together twice, the third time bosomed in

the future. So birds may lend their church,

sown

in air, realized in the body uttering

windows, growing rafters, couching seeds. |

It's from Transforming Vision:

Writers on Art,

selected by Edward Hirsch

(Boston: Bullfinch-Little Brown,

1994) |

EATING ALONE

I've pulled the last of the year's young onions.

The garden is bare now. The ground is cold,

brown and old. What is left of the day

flames

in the maples at the corner of my

eye. I turn, a cardinal vanishes.

By the cellar door, I wash the onions,

then drink from the icy metal spigot.

Once, years back, I walked beside my father

among the windfall pears. I can't recall

our words. We may have strolled in silence.

But

I still see him bend that way-left hand braced

on knee, creaky-to lift and hold to my

eye a rotten pear. In it, a hornet

spun crazily, glazed in slow, glistening juice.

It was my father I saw this morning

waving to me from the trees. I almost

called to him, until I came close enough

to see the shovel, leaning where I had

left it, in the flickering, deep green shade.

White rice steaming, almost done. Sweet

green peas

fried in onions. Shrimp braised in sesame

oil and garlic. And my own loneliness.

What more could 1, a young man, want.

I ASK MY MOTHER TO SING

She begins, and my grandmother joins her.

Mother and daughter sing like young girls.

If my father were alive, he would play

his accordion and sway like a boat.

I've never been in Peking, or the Summer Palace,

nor stood on the great Stone Boat to watch

the rain begin on Kuen Ming Lake, the picnickers

running away in the grass.

But I love to hear it sung;

how the waterlilies fill with rain until

they overturn, spilling water into water,

then rock back, and fill with more,

Both women have begun to cry.

But neither stops her song.

VISIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS

Because this graveyard is a hill,

I must climb up to see my dead,

stopping once midway to rest

beside this tree.

It was here, between the anticipation

of exhaustion, and exhaustion,

between vale and peak,

my father came down to me

and we climbed arm in arm to the top.

He cradled the bouquet I'd brought,

and 1, a good son, never mentioned his grave,

erect like a door behind him.

And it was here, one summer day, I sat down

to read an old book. When I looked up

from the noon-lit page, I saw a vision

of a world about to come, and a world about to

go.

Truth is, I've not seen my father

since he died, and, no, the dead

do not walk arm in arm with me.

If I carry flowers to them, I do so without their

help,

the blossoms not always bright, torch-like,

but often heavy as sodden newspaper.

Truth is, I came here with my son one day,

and we rested against this tree,

and I fell asleep, and dreamed

a dream which, upon my boy waking me, I told.

Neither of us understood.

Then we went up.

Even this is not accurate.

Let me begin again:

Between two griefs, a tree.

Between my hands, white chrysanthemums, yellow

chrysanthemums.

The old book I finished reading

I've since read again and again.

And what was far grows near,

and what is near grows more dear,

and all of my visions and interpretations

depend on what I see,

and between my eyes is always

the rain, the migrant rain.

For a New Citizen of These United States

Forgive me for thinking I saw

the irregular postage stamp of death;

a black moth the size of my left

thumbnail is all I've trapped in the damask.

There is no need for alarm. And

there is no need for sadness, if

the rain at the window now reminds you

of nothing; not even of that

parlor, long like a nave, where cloud-shadow,

wing-shadow, where father-shadow

continually confused the light. In flight,

leaf-throng and, later, soldiers and

flags deepened those windows to submarine.

But you don't remember, I know,

so I won't mention that house where Chung hid,

Lin wizened, you languished, and Ming-

Ming hush-hushed us with small song. And

since you

don't recall the missionary

bells chiming the hour, or those words whose

sounds

alone exhaust the heart-garden,

heaven, amen-I'll mention none of it.

After all, it was just our life,

merely years in a book of years. It was

1960, and we stood with

the other families on a crowded

railroad platform. The trains came, then

the rains, and then we got separated.

And in the interval between

familiar faces, events occurred, which

one of us faithfully pencilled

in a day-book bound by a rubber band.

But birds, as you say, fly forward.

So I won't show you letters and the shawl

I've so meaninglessly preserved.

And I won't hum along, if you don't, when

our mothers sing Nights in Shanghai.

I won't, each Spring, each time I smell lilac,

recall my mother, patiently

stitching money inside my coat lining,

if you don't remember your mother

preparing for your own escape.

After all, it was only our

life, our life and its forgetting.

***The poems are from Lee's book

Rose (Brockport, NY: Boa, 1986); poem number 9 is from The City

in Which I Love You; poem is

from Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, selected by Edward Hirsch

(Boston: Bullfinch-Little Brown, 1994).

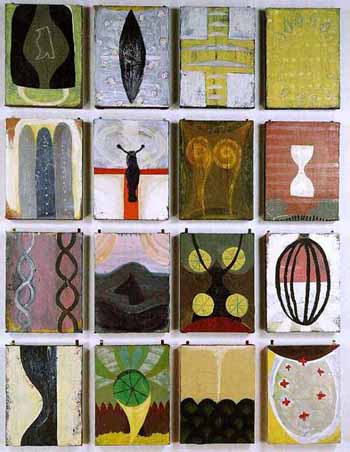

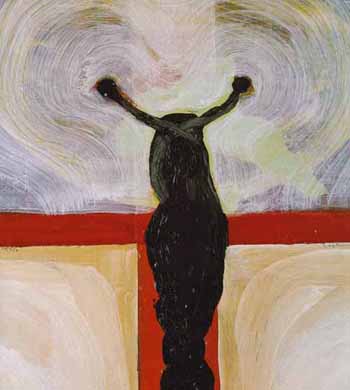

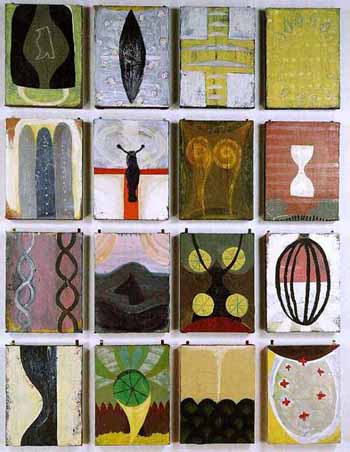

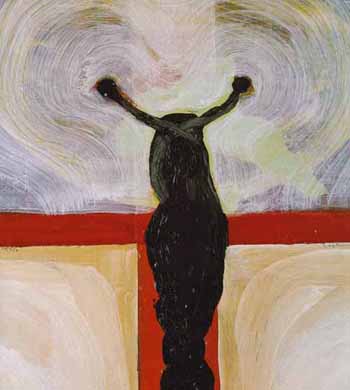

***The background is a print

called "Sacrament and Sorrow" done by Li-young Lee's brother Li Lin Lee.

It's from Crown

Point Press.

SACRAMENT AND SORROW, 1989/Color woocut on silk mounted on rag paper/23

x 21-1/2", edition 25

back to ¡@¡@ ¡@¡@

¡@¡@ ¡@¡@

¡@¡@ ¡@Li-young

Lee

¡@Li-young

Lee