Now can you see the monument? It is of wood

built somewhat like a box. No. Built

like several boxes in descending sizes

one above the other.

Each is turned half-way round so that

its corners point toward the sides

of the one below and the angles alternate.

Then on the topmost cube is set

a sort of fleur-de-lys of weathered wood,

long petals of board, pierced with odd holes,

four-sided, stiff, ecclesiastical.

From it four thin, warped poles spring out,

(slanted like fishing-poles or flag-poles)

and from them jig-saw work hangs down,

four lines of vaguely whittled ornament

over the edges of the boxes

to the ground.

The monument is one-third set against

a sea; two-thirds against a sky.

The view is geared

(that is, the view's perspective)

so low there is no "far away,"

and we are far away within the view.

A sea of narrow, horizontal boards

lies out behind our lonely monument,

its long grains alternating right and left

like floor-boards-spotted, swarming-still,

and motionless. A sky runs parallel,

and it is palings, coarser than the sea's:

splintery sunlight and long-fibred clouds.

"Why does that strange sea make no sound?

Is it because we're far away?

Where are we? Are we in Asia Minor,

or in Mongolia?"

An ancient promontory,

an ancient principality whose artist-prince

might have wanted to build a monument

to mark a tomb or boundary, or make

a melancholy or romantic scene of it ...

"But that queer sea looks made of wood,

half-shining, like a driftwood sea.

And the sky looks wooden, grained with cloud.

It's like a stage-set; it is all so flat!

Those clouds are full of glistening splinters!

What is that?"

It is the monument.

"It's piled-up boxes,

outlined with shoddy fret-work, half-fallen off,

cracked and unpainted. It looks old."

-The strong sunlight, the wind from the sea,

all the conditions of its existence,

may have flaked off the paint, if ever it was painted,

and made it homelier than it was.

"Why did you bring me here to see it?

A temple of crates in cramped and crated scenery,

what can it prove?

I am tired of breathing this eroded air,

this dryness in which the monument is cracking."

It is an artifact

of wood. Wood holds together better

than sea or cloud or sand could by itself,

much better than real sea or sand or cloud.

It chose that way to grow and not to move.

The monument's an object, yet those decorations,

carelessly nailed, looking like nothing at all,

give it away as having life, and wishing;

wanting to be a monument, to cherish something.

The crudest scroll-work says "commemorate,"

while once each day the light goes around it

like a prowling animal,

or the rain falls on it, or the wind blows into it.

It may be solid, may be hollow.

The bones of the artist-prince may be inside

or far away on even drier soil.

But roughly but adequately it can shelter

what is within (which after all

cannot have been intended to be seen).

It is the beginning of a painting,

a piece of sculpture, or poem, or monument,

and all of wood. Watch it closely.

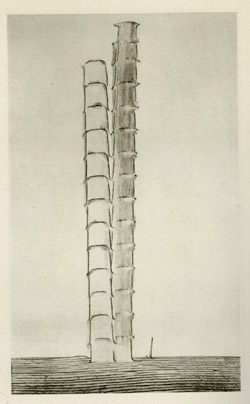

"False Positions" by Marx Ernst in Ernst's book Historire Naturelle from 1926. |

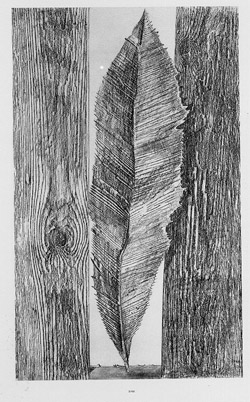

"The Habit of Leaves" by Marx Ernst in Ernst's book Historire Naturelle from 1926. |

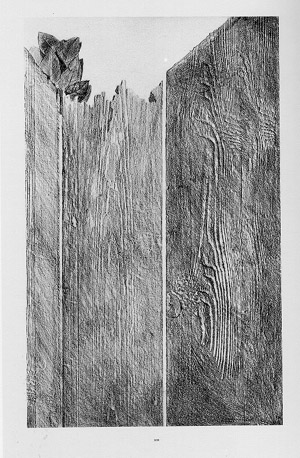

"Shaving the Walls" by Marx Ernst in Ernst's book Historire Naturelle from 1926. |