|

|

|

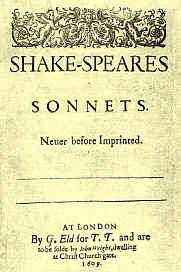

Introduction to Shakespearean Sonnets

The two main

forms of the sonnet are the Petrarchan (Italian) and the Shakespearean (English). Sonnets had been glorified by Petrarch in Italy

more than 200 years before English poets even knew about them. William Shakespeare's first

and second years in London were spent writing in the Petrarchan style. The Petrarchan

sonnet has an eight-line stanza, or octave, and six-line stanza, or sestet. The octave has

two quatrains, rhyming abba, abba, but

avoiding a couplet; the first quatrain gives the theme, and the second develops it. The

sestet is built on two or three different rhymes; the first three lines reflect on the

theme, and the last three lines bring the whole poem to an end. It differs from the Petrarchan sonnets in that it is

divided into three quatrains, each rhymed differently, with an independently rhymed

couplet at the end. The rhyme scheme of the

English sonnet is abab, cdcd, efef, gg. Each

quatrain takes a different appearance of the idea or develops a different image to express

the theme. All of Shakespeare's 154 sonnets

were in this form except for the poems he wrote earlier in life. The sonnets appear to extend from 1593 or 1594

until within a few years of their actual publication in 1609. His cycle is quite unlike the other sonnet

sequences of his day, notably in its idealization of a young man (rather than a sonnet

lady) as the object of praise, love, and devotion and in its portrait of a dark, sensuous,

and sexually promiscuous mistress (rather than the usual chaste and aloof blond beauty). Nor are the moods confined to what the Renaissance

thought were those of the despairing Petrarchan lover: they include delight, pride,

melancholy, shame, disgust, and fear. Shakespeare's sequence suggests a story, although

the details are vague, and there is even doubt whether the sonnets as published are in the

correct order. One hundred and one sonnets

were written to a young man. These have

variety of themes, such as the beauty of the loved one; destruction of beauty; competition

with a Rival Poet; despair about the absence of a loved one; and reaction toward the young

man's coldness.

Example: (Sonnet78) So

oft have I invoked thee for my Muse, (A) And

found such faire assistance in my verse, (B) As

every Alien pen hath got my use, (A) And

under thee their poesy disperse. (B) Thine

eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing, (C) And

heavy ignorance aloft to flie, (D) Have

added feathers to the learned's wing, (C) And

given grace a double majestie. (D) Yet

be most proud of that which I compile, (E) Whose

influence is thine and born of thee, (F) In

others' works thou dost but mend the style (E) And

arts with thy sweet graces graced be. (F) But

thou art all my art, and dost advance (G) As high as learning my rude ignorance. (G) Sonnet 78

(above) is typical of Shakespeare's use of the English form of the sonnet with its rhyme

scheme of abab cdcd efef gg. In sonnet 78, the

first few lines reflect on the theme of his writings, and the last two lines bring the

sonnet to a conclusion. This sonnet clearly shows that Southhamptons (another poet who

later became a rival) is giving help to one or more rivals.

(1) Shakespearean Sonnets A

Shakespearean sonnet has three quatrains and a couplet, and rhymes abab cdcd efef gg. A

Shakespearean sonnet frequently introduces a subject in the first quatrain, expands it in

the second, and once more in the third, and concludes in the couplet. Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnets An Italian sonnet is composed of an octave, rhyming

abbaabba, and a sestet, rhyming cdecde or cdcdcd, or in some variant pattern, but with no

closing couplet. In both types, the content tends to follow the formal outline suggested

by rhyme linkage, giving two divisions to the thought of an Italian sonnet and four to a

Shakespearean one. The Italian sonnet develops and idea through eight lines and then

pauses, creating a turn or volta, before the concluding six.

Sonnet 1 to 17: Celebrates the beauty of a young man and urges him to

marry so as to propagate and preserve that beauty. Sonnet 18 to

126: The subsequent long sequence focuses on (probably) the

same ideal young man, developing as a dominant motif the transience and destructive power

of time, countered only by the force of love and friendship and the permanence of poetry. Sonnet 127 to

154: Focus on the so-called Dark Lady as a tempting but

degrading object of desire. Some sonnets (like 144) intimate a love triangle involving the

speaker, the male friend, and the woman; others take note of a rival poet (sometimes

identified as George Chapman or Christopher Marlowe). ˇ@ |