|

參加二次世界大戰勝利慶典的一群華人婦女 一九四五年 (加拿大國家檔案館惠借﹐加拿大駐台北貿易辦事處提供) |

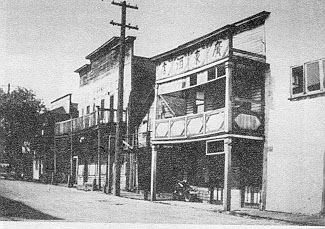

The Canton House (廣東酒家) in Nanaimo's Chinatown years after May-ying worked there (The Concubine's Children). |

Chinatown-- four stages: budding, blooming, withering, extinction or reviving

In the old days, Chinatown was regarded by the white community as a segregated, mysterious ghetto of prostitution, gambling, opium-smoking, and other vices, but it was considered by the Chinese people as a home where they could find pleasure, comfort, and companionship; it was a sanctuary where they were secure from threats and discrimination. (Lai xv)

|

Vancouver 10/1(5,790 males and 585 females) Edmonton 30/1 (501 males and 17 females) Regina 60/1 (246 males and 4 females) Ottawa 30/1 (273 males and 9 females) Halifax 60/1 (138 males and 2 females) |

|

Through the years of Head Tax, the Exclusion Act, the Depression and the two World Wars, daughters speak of watching their mothers working endlessly. They themselves often experienced a double load of work and school. Social life was very limited. . . However, these hardships forstered a new and more intimate relationship between mothers and daughters. Many of the older women spoke little of no Enlgish and had few friends. In their isolation they turned to their daughters for comfort and help coping with the new society. Children acted as their mothers' eyes and ears--their communication link to the outside world. ...Reading the words of these women, we were struck by the lack of bitterness or regret. What does come through, however, is their quiet resolve for a better life for their children and grandchildren. ...(Jin Guo 20) Literary Treatments: The Concubine's Chidren, Disappearing Moon Cafe |

|

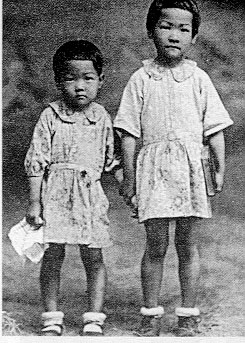

"Made in Canada." Left: The concubine's eldest daughters, Ping and Nan, on Chinese soil |

|

|

Left: The photograph

which stood on May-ying's dresser alongside the one of her youngest, Hing

(right), taken in a Vancouver studio. So taken was May-ying with

dressing her as a boy that she commissioned a portrait; in the original,

mother and daughter stood hand in hand.

|

Winnie and her father leave for the church. Winnie and her mother |

|

|